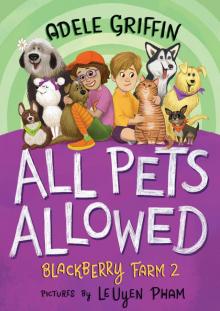

All Pets Allowed

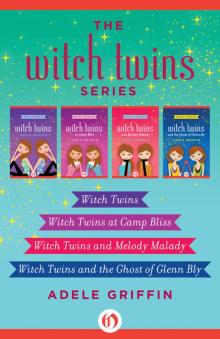

All Pets Allowed Witch Twins Series

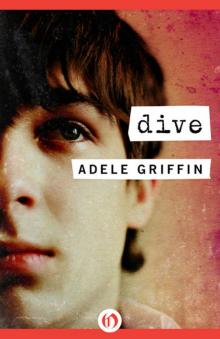

Witch Twins Series Dive

Dive V is for...Vampire

V is for...Vampire Amandine

Amandine The Knaveheart's Curse

The Knaveheart's Curse Picture the Dead

Picture the Dead My Almost Epic Summer

My Almost Epic Summer Sons of Liberty

Sons of Liberty Overnight

Overnight Witch Twins

Witch Twins Witch Twins and the Ghost of Glenn Bly

Witch Twins and the Ghost of Glenn Bly The Julian Game

The Julian Game Other Shepards

Other Shepards Split Just Right

Split Just Right Vampire Island

Vampire Island Rainy Season

Rainy Season Hannah, Divided

Hannah, Divided Where I Want to Be

Where I Want to Be Be True to Me

Be True to Me Witch Twins at Camp Bliss

Witch Twins at Camp Bliss Tell Me No Lies

Tell Me No Lies The Unfinished Life of Addison Stone

The Unfinished Life of Addison Stone